ESSENTIAL READING

Unai Emery’s Time Is Up

Unai Emery has proven he is not capable of reviving Arsenal. It is time for the club to begin the process of finding someone who can.

In Arsene Wenger’s final few years as Arsenal manager, it became hard to keep track of the number of matches that felt like a new nadir; a blow that couldn’t be recovered from. There were the multiple bloated defeats to big teams away from home, that cumulated in the 10-2 aggregate defeat to Bayern Munich, still Arsenal’s most recent participation in the Champions League. Then in the final couple of seasons there were several pathetic defeats away from home to mid-table and relegation battling teams. A 3-1 at West Brom in March 2017. A 3-0 at Palace a month later. A 2-1 and 3-1 at Bournemouth and Swansea in January 2018. The 2-1 in Brighton that March.

For some Arsenal’s defeat to Sheffield United on Monday will be that nadir with Unai Emery. For others it would’ve been the Europa League final against Chelsea, or perhaps the atrocious second half at Watford in September. And for some, that match will still be to come. For myself, however, things are a bit different. Throughout Emery’s tenure there hasn’t been a moment of breaking point, where it felt like time. Yet it is nonetheless just as clear as it was in March 2018, perhaps even more so, that Arsenal’s current manager is not the person to take the team forward in the foreseeable future.

Of course there have been some real low points. More problematic for Emery, however, is less the depths of the nadirs and more that, after 70 games in charge, it’s very hard to find any bright sparks or reasons for optimism when it comes to his management. For more than 14 months Arsenal have been consistently playing mediocre football under their current head coach. The particularly severe problems of the final two Wenger seasons - Arsenal’s defending and away performances - haven’t been improved in the slightest, and it’s come alongside a decline in their attacking cohesion and authority in possession.

In total Emery has had 47 Premier League games and if you were to count the number of genuinely convincing performances you’d struggle to reach double figures. There haven’t been any yet this season, and they were sparse enough last term. The wins at home against Tottenham and Chelsea were the clear highs and Arsenal were unlucky to only draw away at Tottenham in what was their most accomplished performance away to a big six team in years. A 1-1 draw vs Liverpool was a fine showing against a great team. There was a fantastic second half at home to Leicester and a great first half at home to Southampton. Fulham were twice dispatched, and Bournemouth were comfortably put away at home.

Arsenal’s other league wins have usually fallen into one of two categories. Either Arsenal struggle to control or breakdown a weak team and have to battle for a scrappy win - Huddersfield and Cardiff twice last season, Bournemouth and Aston Villa at home this season, among many examples. Or Arsenal have played their opponents about even, and have come out on top through being more clinical with their chances, rather than any dominance in general play - Everton, Watford and Manchester United at home last season were the clearest examples.

There have been some baffling tactical decisions, like going with a diamond at Anfield when Liverpool do so much of their attacking through their fullbacks. Emery has spoken about making Arsenal a chameleon team tactically, an idea that isn’t without its merits. In practice, however, it has been difficult to grasp the logic behind Emery’s chopping and changing. The number of half time substitutions (25 in the league) have added to the sense that Emery is fumbling in the dark for tactics and combinations that work, rather than executing them with a clear thought process.

For many, their biggest gripe with Emery is his loyalty to certain players, or his lack of trust in others. His unwillingness to use Torreira as a base midfielder, where he played for Sampdoria and still does for Uruguay, and his preference for the Xhaka and Guendouzi pivot instead, is just one example in this regard.

- - - - - -

In truth, these kind of complaints could go for a while, and everyone has their own; but these micro tactical and selection issues people have with Emery are minor compared to the major macro issues of his time at Arsenal so far.

There have essentially been three major failings of Emery as a coach in his tenure so far. The first of those has been his inability to build a coherent attack. Quickly after he took over it became apparent that Arsenal, either through deliberate design or simply an inability, weren’t sustaining pressure in the final third as much as they did under Wenger. For a while this was somewhat counter balanced by the fact Arsenal had slightly improved in their bringing the ball out from the back in a more structured and precise manner. [I wrote more last November about how Wenger wanted to get the ball up the pitch as quickly as possible, while Emery liked to focus on the earlier phases]. This meant the Gunners were able to score a few very well worked goals that started from the centre backs or goalkeeper. As time wore on, however, the attacking fluidity and final third combinations that were a constant trademark of the Wenger years continued to deteriorate. Having a better system to get the ball to the midfielders or fullbacks up the pitch is useless if you don’t know what to do with it in the final third.

This has been exasperated by the fact Emery hasn’t been able to implement many of his own attacking automatisms or player partnerships that influence how the team plays. In the early months there was more focus on fullback overlaps and cutbacks, and in the winter of last season Alex Iwobi built a partnership with Sead Kolasinac that bore some fruit until the former’s sale. Admittedly it’s early days, but there aren’t yet many signs of attacking combinations involving the new faces in Arsenal’s midfield and attack. Nicolas Pépé and Bukayo Saka have created chances for Aubameyang, which almost goes without saying, but it’s not clear which players are likely to find their runs, or play 1-2s with them. The returning fullbacks, Kieren Tierney and Hector Bellerin probably have the most potential to strike up partnerships with them, but given what we’ve seen of Emery’s Arsenal so far, it would be naive to genuinely expect it.

Of course Arsenal still score goals and are a better attacking team than they are a defensive one. But none of that is a surprise considering the attacking firepower they have. Arsenal’s four record signings are all attacking players in the current squad. Being able to score and outgun teams with their attack should be the bare minimum of the Gunners’ expectations.

Related to the inability to sustain attacks comes the second major failing of Emery’s reign; Arsenal simply don’t control or dominate games as much you’d expect when they play theoretically inferior opposition. Arsenal games tend to either be open and like basketball matches - end to end with each team taking it in turn to attack - or turgid affairs with few shots or quality attacking moves - Monday’s loss in Sheffield, a prime example of the latter. Arsenal don’t suffocate teams with dominate possession, nor do they press with much intensity to win the ball. It’s a bad combo. In his first press conference as manager, the Spaniard claimed he wanted Arsenal to be “protagonists in possession and the pressing” but this plainly hasn’t been carried out.

One attempt at measuring pressing is PPDA which divides the number of passes the opposition are able to make in their own half, by the number of defensive actions a team makes. Generally the lower the figure, the more successful a side was in disrupting their opponents possession through pressing, while a higher figure suggests a more passive approach. Last season in the Premier League Man City had the lowest figure, while Bournemouth had the highest. Rather than becoming more intense and coherent, Arsenal’s PPDA has slightly increased since Emery took over, which implies Arsenal are more content to allow opposition teams to keep the ball away from goal. The trend is moving further towards that as well, the away games to Liverpool and Watford this season represent two of the three highest PPDA figures for single Arsenal matches since 14/15 begun.

This goes with what The Athletic reported last month, with James McNicholas claiming that any focus on pressing in training didn’t last beyond the very early stages of Emery’s reign.

https://theathletic.com/1216532/2019/09/17/emery-is-unloved-and-under-threat-it-may-be-time-for-the-next-man/ (to sign up use theathletic.com/arsenalvision)

There are valid reasons to play a more passive defensive game, and to look to attack with speed rather than play keep ball when you get it. In fact, it seems likely that Emery came to this conclusion and believes it to be the best way for Arsenal to play. But to say Arsenal’s tactics haven’t worked would be an understatement. Since Emery took over Arsenal have faced 58 more shots than they’ve taken in league play. This is practically unheard of for top four contenders. For context, in the same period Man City, Liverpool and Chelsea have shot differentials of +570, +324 and +329 respectively, while Arsenal in 17/18 (just 38 games, not 47) had a positive differential of 172. While it’s true the quality of Arsenal’s shots taken are higher than the quality of shots they allow, it’s not by a significant enough margin to override such a terrible differential.

I slipped in a graphic earlier while talking about the attack under Emery. It showed the number of deep pass completions (defined as passes that end up fewer than 20 yards from goal) the Gunners have made on average in the last few Premier League seasons. Not surprisingly there’s a slump that occurs not long after Emery takes over. Arsenal simply complete fewer passes into the last part of the pitch now than they did at any point under Wenger in the last few seasons. The trend is also the opposite in defence. Arsenal are conceding more passes per match into deep zones than under Wenger. Quite simply, since Emery’s arrival, Arsenal fans have been seeing less action in the opposition box and more action in their own than they used to.

What makes things more frustrating is that the players Emery selects could feasibly be more suited to another style. Granit Xhaka is a flawed player, but he is not without his qualities. He is a well above average passer in possession, and can be a significant plus to a side playing a possession game, as he has been for Arsenal on occasions in the past. What he clearly lacks is the defensive intelligence and mobility to be a great screener of the back line out of possession. This makes Emery’s method of trying to see out games through control without the ball particularly bizarre. There’s ample evidence showing it doesn’t work and the players are ill-suited to it.

This is all connected to the third major problem under Emery; Arsenal’s continued defensive failings. People could look past less cohesion in attack, less dominance through possession, less aggressive pressing and more conservative team selections if it had helped to solve Arsenal’s three year defensive crisis. Indeed there are those that do defend Emery on the grounds that Wenger’s football and team selections were simply leaving the team too open. But defensively there hasn’t been any improvement since Emery took over.

In the wider media there’s a bit of a myth that Arsenal have always been a bad defensive team in the period since their last league title. But for years Arsenal had been exactly what you’d expect from the third or fourth best team in the league defensively. In 12/13 they conceded the second fewest goals in the league. In 13/14 they conceded 41, but 20 of those were in four games. In the 34 games that weren’t away to top five teams, they conceded only 21 goals, a stellar defensive performance. In 15/16 they had the lowest xG against in the Premier League, and would’ve competed harder for the title had Petr Cech not shown a surprising weakness to long shots at his near post that season.

Arsenal’s defence only became truly bad in 16/17, when Arsenal’s xG against was more than 13 goals higher than the previous season. A year later it was even worse, and Arsenal conceded 51 goals, a record for the club in the Premier League era. In Emery’s first season they repeated the trick, matching the 51 goals conceded of the previous season. This was despite Emery getting new signings in goal, at centre back, and in defensive midfield. Leno also did his job well, and was arguably one of Arsenal’s three outstanding players last season alongside the two strikers. Arsenal actually over performed their xG allowed by more than six goals while conceding 51. This season it’s not been better. If they continue to ship chances at their current rate, Arsenal are likely to end the season conceding 58 goals in the league. In short, the defence has deteriorated so much, that Arsenal are conceding chances at a rate of 25 goals a season more than they were just three and a half years ago.

- - - - - -

There are those that argue the task of replacing Wenger was never going to be a quick and easy task, and that with more time and investment, Emery could form Arsenal into a formidable side. While there is truth in the former statement, at this point there just isn’t sufficient reason to believe Arsenal will make any significant improvement as a result of Emery’s coaching. The returns of Bellerin and Tierney at fullback could feasibly help Arsenal in all aspects of play. Signing more good players in future transfer windows could help Arsenal get better results - though the results this season show even that is in doubt. But after two pre-seasons and over 15 months of training time to implement his vision and philosophy on the squad, what reason is there to think Emery will eventually coax more out of the players he has so far got little from?

One of the concerns that surrounded Emery before he took over was the type of clubs he’d had most success at. The easy joke, and an unfair one in truth, was that he was a Europa League specialist. The more nuanced criticism was that in his time at Valencia and Sevilla Emery’s success had come from achieving consistently solid results, never from elevating them to a level above their resources. Now obviously doing that is difficult and extremely rare even for good managers. It does, however, stand as a key point to differentiate Emery from someone like Jurgen Klopp - often cited by Arsenal fans as an example of what can happen when you give a manager time - who had a history of lifting a sleeping giant in Borussia Dortmund to title wins and a Champions League final.

If one were to be particularly harsh of Emery’s time at Arsenal - and it’s not particularly necessary to be so to make a case against him given the realities laid out so far - one could go as far as to suggest Arsenal’s best bits of performance since he took over have actually had the least to do with his coaching. In the early months of his reign, Arsenal usually had sluggish first halves, only to get the result when going more full throttle in the second half. At the time it felt like the players were having more success when throwing caution to the wind and letting their individual quality take over than when trying to implement Emery’s plan. Around March last season Emery went away from his favoured rigid double pivot and finally deployed Aaron Ramsey in a deeper position. Ramsey added vertically to the midfield and it resulted in one of Arsenal’s best runs of the season with wins over Manchester United and Napoli, until Ramsey’s hamstring injury contributed to the season being derailed. This season Arsenal’s best performances have all come with the second string lineups in the Europa League and League Cup, using players who have had fewer matches and training sessions with Emery than the first team regulars.

Now that is a harsh outlook, and is at best a possibility unlike the earlier criticisms which are all but factual. It does, however, support the idea that Arsenal’s squad isn’t terrible, and that it’s not unreasonable to think their league struggles are down to something other than player quality.

This season’s Europa League performances also bring relevance to the one shinning light for Arsenal football club at the moment. The Gunners have a stack of young players who have looked promising in the minutes given. This is actually a rare area Emery probably has to be given credit, given he could’ve quite easily opted for more experienced starters than the likes of Saka and Joe Willock, or at least fought harder to not lose either of Alex Iwobi and Henrikh Mkhitaryan from his squad. This shows that the long term future doesn’t have to be doom and gloom. It does, however, mean the next stage in Arsenal’s development is crucial. Which makes having a head coach that can maximise attackers and possibility elevate a team beyond the sum of its parts sooner rather than later even more of a priority.

- - - - - -

It should go without saying that none of this is a personal crusade against the man. Regardless of his time at Arsenal Emery has had a very successful managerial career. As Alex Kirkland said on a recent Arsecast, Emery would have no problem finding another job in La Liga and would even be one of the main candidates for next Spain manager. It’s entirely possible his problems at Arsenal have predominantly been an issue of communication. Or perhaps his footballing ideas just don’t gel with this crop of players.

For over 20 years Arsenal fans got to bask in a reality few fans do; one of managerial security. Now they are in the pack with the rest of the world, where managerial turnover is frequent. Many appointments don’t go the way they were initially hoped. Unai Emery’s at Arsenal is one such example. The reality of modern club setups is that they don’t have to be defined by the manager. Much of Arsenal’s backroom changes in the last two years has been for this exact reason, to hold some level of continuity at club level from one managerial appointment to the next.

During the international break David Ornstein confirmed that Arsenal have a clause in Unai Emery’s contract where they can get out of the third year without having to make a pay off. That they should do it if the time arrives is at this point a given. The Arsenal board have the next seven months to start preparing for that situation, and to ponder whether paying the moderate financial sum required to end his tenure before then is worth it. If it comes down to top four or no top four, and the huge financial benefits that come with it. Well, you do the maths.

Understanding Emery Football And The Importance Of A Back Three

Special Contribution by Oscar Wood. Follow him on Twitter @Reunewal.

That's more like it. That’s what we've been waiting for. Sunday’s North London derby win didn't just give Arsenal their first landmark win of the new era, it also helped give us our clearest indication yet of what it is Unai Emery is trying to achieve on the pitch with this squad. Despite results so far this season being positive, it's hard to escape the feeling a performance such as this was needed for us to get a clear view of what a working Emery Arsenal team looks like.

I think one difficulty Emery has had since joining is that, compared to many of his Premier League compatriots right now, he isn’t as renowned for a particular style of play, nor is what he tries to get his teams doing considered innovative. When Jurgen Klopp, Pep Guardiola and Maurizio Sarri arrived at their clubs they began implementing stylistic overhauls that could easily be observed while watching a single game or making cursory glance at the statistics. With Emery the changes have been more subtle. Arsenal have predominantly still lined up in a variation of 4-2-3-1, they still try to control the ball and build through the thirds and still rely on quick combination play to break teams down.

In fact it’s arguable Emery’s biggest impact so far hasn’t been tactical, it’s been in the physical conditioning of his players, which has helped allow an improved level of intensity on the pitch. Heavy pre-season training sessions and pre-match sessions taking place at kick-off time have clearly contributed to the fact Arsenal have never looked physically outmatched this season (something they often did in previous years) and probably goes someway to explaining their quite incredible second half record this season.

Possession Structure

All that doesn’t mean Emery hasn’t made his own tweaks, however. The most clear tactical shift Emery has made has been in Arsenal’s possession structure. While many modern coaches put an immense amount of focus on the first phase of build up (i.e. the goalkeeper and defenders moving the ball to the midfield) it’s easy to get the sense Arsene Wenger always considered it all a bit tedious. Wenger’s priority in build up was usually to move the ball forward as quickly as possible, to maximise the amount of time the attacking midfielders could spend on the ball in the opposition half.

Anam Hassan has talked extensively about how Wenger would ask his midfielders to push further up the pitch, in an attempt to discourage the opposition from pressing and instead pin them back. Needless to say, this was a high risk, high reward strategy. When it worked Arsenal’s best creative players where able to enjoy lots of the ball, but against stronger pressing opponents Arsenal would regularly come unstuck.

Emery’s play from the back (when using a back four, which he’s done for the majority of the season) is built around the two centre backs and two central midfielders. Probably the most distinctive feature of Emery’s time at Sevilla was his love for a solid double pivot. That trend has been continued at Arsenal. While Wenger liked a clear division of labour between his two central midfielders, often partnering a defensive minded player with a more attacking one like Aaron Ramsey, Emery likes his midfielders to share their buildup and defensive duties. Granit Xhaka, Lucas Torreira and Matteo Guendouzi have been exclusively used in midfield in the Premier League and are all are comfortable acting as a single defensive midfielder. As such Arsenal will often rotate as to which midfielder drops in between the CBs during build up.

The counter to this use of the central midfielders is that the attacking midfielders are instructed to stay high and maintain the team’s shape, rather than dropping deep to help progress the ball themselves. Under Wenger it was common to see the likes of Mesut Özil, and other attacking midfielders, dropping deep, and a midfielder like Ramsey running forward into the vacated space. Such midfield rotations have become effectively extinct under Emery. While pass maps have significant limitations - mainly because they only show a player’s average touch position, not their off ball position - the Arsenal one against Liverpool nicely outlines a typical structure in Arsenal’s 4-2-3-1. There is a clear divide between the central midfielders and attacking midfielders and the fullbacks are getting on the ball in advanced areas.

So far the results of this more meticulous build up play have been mixed. While Arsenal have scored plenty of goals, for most of the season they’ve had the majority of their success in brief spells of dominance, rather than as a constant threat. The odd beautiful goal and five minutes of brilliance has often been preluded with a period where the team has looked ponderous. In fact, one potential reason Arsenal have been so much better in second halves might be that it’s when they’ve released the handbrake, to borrow a Wengerism, and played with greater urgency and freedom that they’ve found their attacking grove.

There have been moments, however, where Arsenal have executed what we might begin to associate as trademark Emery Arsenal. If Wenger football was about getting into opposition territory as quickly as possible then perfect Emery football might be the opposite; a precise build up leading to a fast transition once the ball is played into one of the attackers. The fantastic team goals against Fulham and Leicester are examples, as is this move against Liverpool, where the goalkeeper, both centre backs and both central midfielders are involved.

Aggressive Pressing

Arsenal fans were understandably excited when Unai Emery promised protagonism with and without the ball, and a desire for intensity in pressing. But so far this season Arsenal haven’t show signs of being a particularly aggressive pressing side. This may be down to Emery not believing the squad were ready to successfully implement a very aggressive press, and that there were other issues that needed attention first. Or it could be that he knows what fans like to hear and wanted to start on the good side of Arsenal’s supporters, regardless of his plans for the team.

On Sunday, however, Arsenal put in their most aggressive, and most impressive, pressing performance of the season. That this correlated with Arsenal’s best start to a Premier League match under Emery is likely no coincidence.

Analysing or measuring a press is difficult, because what you’re attempting to analyse is the impact on the opposition rather than something purely to do with your own team, and it can be hard to separate your team’s influence from their own game plan. For example one such measure is the opposition pass accuracy, but when it comes to opponents like Cardiff, who almost always have a poor pass accuracy, it’s hard to argue Arsenal did something specifically that prevented them completing passes. The best measure is probably the number of opposition passes played per Arsenal defensive action (PPDA). This essentially gives you a value for the number of passes a team was able to put together before being engaged in a tackle, interception or foul. Against Tottenham Arsenal recorded their joint lowest PPDA of the season (5.43) meaning Tottenham were rarely able to string long passing sequences together before being engaged by Arsenal pressure.

At 72%, Tottenham also recorded the fifth lowest pass accuracy by any of Arsenal’s 14 opponents this season, and the lowest of anyone currently in the top half. Both Spurs CBs, and Eric Dier, recorded pass accuracies in the 60s, and were regularly forced into hitting harmless long balls up the field instead of building play from the back how they’d like.

Regardless of the level of pressure it’s clear one of the hallmarks of Emery’s philosophy is a high work rate and intensity in his team’s play (Arsenal have regularly been at the forefront of most running stats this season). Sunday showed that, at the right moments, that philosophy can go one step further and be used to implement aggressive and successful pressing plans as well. It’s here where Arsenal can also benefit from the depths of their squad. Whether Emery planned to make a double substitution as early as half time is debatable, but it’s likely Iwobi and Mkhitaryan were went out in the first half with the knowledge they wouldn’t be playing the full 90 minutes, and could thus play above and beyond while they were on the pitch.

Could A Three At The Back Kill Two Birds With One Stone For Arsenal?

Much of the Arsenal discourse in the last couple of months has centred around the impact of Lucas Torreira, and how he’s helped make Arsenal a much more resilient and solid side. While the Uruguayan himself has played at a fine level since becoming a regular starter, the transformative nature of his arrival has perhaps been a bit overstated. Arsenal are still conceding chances. The 18 goals against in 14 matches isn’t itself a particularly good figure, and it could’ve been worse if not for some fine goalkeeping performances from Bernd Leno. The nature of these chances has also been of concern. Before the trip to Bournemouth Arsenal had faced the joint most counter attack shots in the division, along with West Ham and Manchester United. The match against Wolves before the international break showcased the worst of it. The visitors took the lead following a fast break on a turnover, and had multiple chances to add a second on transition.

Arsenal’s opponents have attacked down the middle less this season, 24% of the time compared to 27% last term, which suggests Arsenal’s double pivot might be doing a better job of blocking the middle of the pitch. But this has been counted with a more attacking use of the fullbacks. Arsenal have been particularly vulnerable down the left at times this season. They’ve tended to have a bias towards that side while attacking, mainly because the left footers Xhaka and Özil are more comfortable passing to their left and operating in those zones, which means the players on the left have to push further up the pitch. Given the defenders on the left - Xhaka and Monreal or Kolasinac - are not as athletic as the ones on the right - Bellerin and Torreira - this can be a problem. It’s also possible that, despite clearly not being the player he once was last season, Laurent Koscielny was still an improvement in defence over Sokratis and Rob Holding, and that the change in CB pairing has mitigated the improved defensive performance in Arsenal’s midfield.

Three at the back could help both this problems. Having three players allows the wing backs to get forward the way Emery likes, and allows an extra body to help defend the channels in transition. Additionally simply having three centre backs could also help to somewhat mitigate the fact they’re not of the highest individual level.

In the first 15 minutes at Bournemouth Arsenal seemed to be struggling with the system. Bournemouth attacked with a front four meaning Arsenal got pinned into a back five and struggled to get out with a lack of outlets. There also seemed to be an uncertainty amongst the back five about each others roles, what with Arsenal not having used the system since February. They were possibly fortunate that a marginal offside went their away in that period, but since then they have put in two of their best defensive displays this season. Against Bournemouth and Tottenham respectively, two of the best attacking sides in the league, Arsenal conceded just 0.5 and 0.25 expected goals against from open play.

In Attack

While three centre back formations naturally lead to a focus on the defensive structure and setup, they can also help create different attacking shapes. The most obvious being that, with two wing backs, there’s little need to true ‘wingers’, as seen against Bournemouth and the first half on Sunday, when Alex Iwobi and Henrikh Mkhitaryan were used in inside roles. This is where Wenger’s team benefited the most from the move to a back three. Mesut Özil, Alexis Sánchez and Aaron Ramsey were all able to be used in attacking positions behind the striker without sacrificing width or numbers defensively. Much has been made of Arsenal’s lack of genuine wingers, and while neither Hector Bellerin or Saed Kolasinac can take on players 1v1 the way a true wide forward could, they will at least maintain width and offer runs in behind.

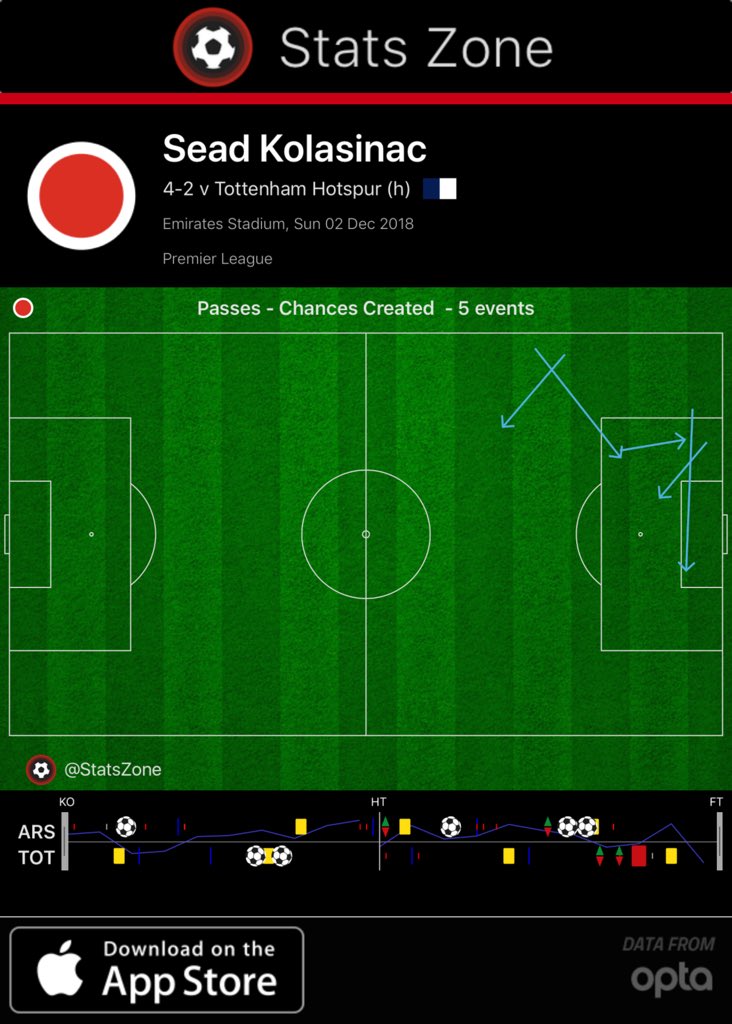

On Sunday, Mauricio Pochettino opted for the midfield diamond that was so successful against Chelsea the week before, but this simply played into Arsenal's hands as the wing backs were afforded even more space. Bellerin was instrumental in Arsenal's possession play, completed the second most passes in the match and helped create the equaliser early in the second half. Kolasinac was the main creative force on the day, creating five chances. No one else from open play created more than two.

To start both fixtures, Emery opted for a clear 3-4-2-1, not a shape that will help get both Aubameyang and Alexandre Lacazette in the side. However, as his substations at half time on Sunday showed, reversing the attack from a 2-1 shape to a 1-2 is simple enough, and playing two strikers doesn’t sacrifice width or midfield numbers as much in a back three. I think Emery probably prefers a 3-4-2-1 to a 3-4-1-2, because he can maintain the two midfielders and two attacking midfielders shape we saw against Liverpool. But the second half against Tottenham proved that he’s happy to go the other way if he believes it’s the best way forward.

In fact, Emery deserves praise for the significant versatility he has shown in recent weeks. After almost exclusively playing 4-2-3-1 all season, from the second half against Wolves onwards, Emery has tried at least three different shapes. While we were having debates on the merits of results vs performances, Emery has tinkered, first with personnel, then with shape, in the knowledge Arsenal had a much greater level they could go to. Such awareness, when it would’ve been easy to stick with the same lineups while the wins were still coming, is a good thing. Only time will tell if these changes will actually pay off in the long term, but the early signs are positive.

Mesut Özil: Unai Emery’s conundrum

This is part two of a three part series on Mesut Ozil by Oscar Wood.

Yesterday we took a detailed dive on Özil’s 2017/18 season.

An interesting aspect of Mesut Özil is that while opinions of him are vulnerable to extreme fluctuations, his performance levels, and the statistical output he produces, are usually strikingly consistent. Such is the quality and repeatability of his core technical and mental attributes - ball control, passing, movement, decision making, vision - he rarely has an outright bad game, where he performs those aforementioned skills poorly (one rare example was actually the opening day against Manchester City, where his final third passing was a letdown). The most common reason for Özil having a mediocre game is usually external; when he’s put in a position where he can’t utilise his strengths and his weaknesses are exposed more. Usually this is when Arsenal struggle to get control of games and he simply doesn’t see as much of the ball as he’d like. In other words, it’s the age old cliche about how he can’t grab a game by the scruff of the neck, unless it’s there for the taking.

This isn’t an issue for him over a sustained period of matches. Or at least, it hasn’t been so far in his career. Of course, like any player, he goes through physical ups and downs as well, meaning sometimes he has better months than others. But, whereas others like Aaron Ramsey and Henrikh Mkhitaryan may often have games where their touch and weight of pass is off, with Özil you usually know what you're going to get. Often his supposed up and down periods are simply down to the nature of assists. The finish is beyond your control and there’ll be periods where the other forwards run hot and periods where they run cold.

All this makes his start to the season all the more alarming. The Arsenal fanbase and wider football world has had many moments of doubt surrounding the German before, but it’s rare that a period of Özil scepticism has been matched with a significant drop off in his statistical performance as well. Arsenal’s number 10 is currently underperforming in virtually every metric, with his creativity and overall passing numbers significantly worse than last season.

While, as mentioned earlier, Özil’s statistics have tended to stay consistent over medium term periods, and we are still very early in the season, the fact Arsenal have a new coach has exasperated fears that Özil’s recent performances could be the start of a new long term trend. Arguably most striking is the drop off in overall involvement. While days can happen where a player fails to create moments of spark, a lack of involvement in possession indicates potential systemic issues. In the Premier League so far this season Özil has completed just 31.1 passes per 90 minutes, less than half of his career high figure in 17/18. To put things into perspective, in a typical game last season only Xhaka would play more passes. This season only Lacazette, Aubameyang and Cech are attempting fewer.

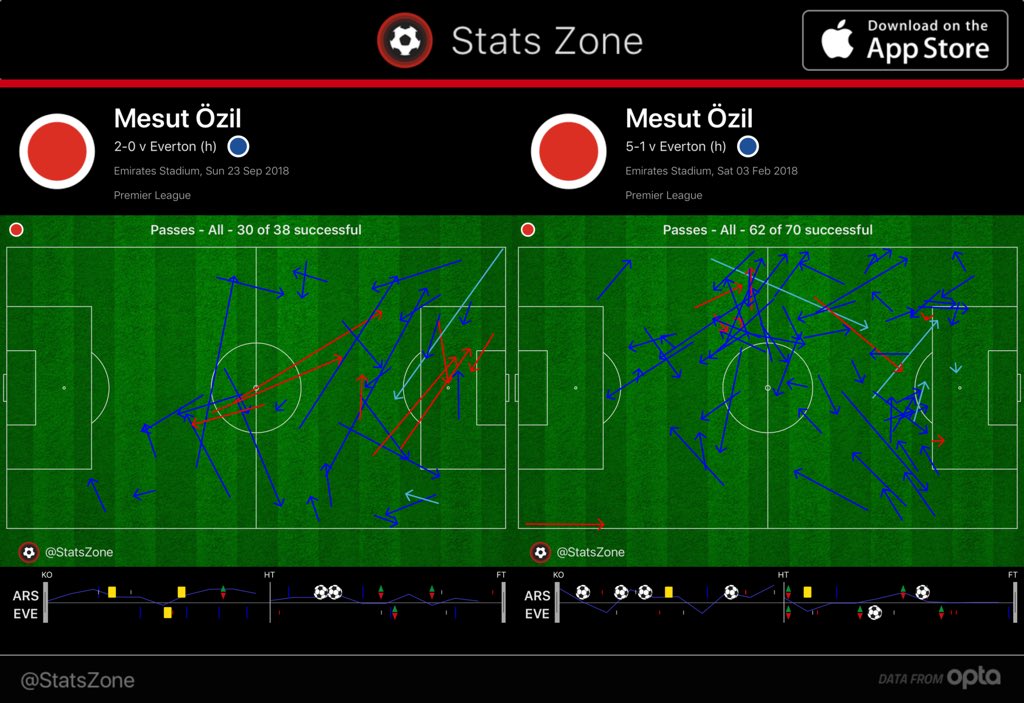

So what factors could be behind Özil’s poor performances this season, and in particular, his lack of involvement compared to previous years? The most obvious change has been in his starting position. Emery has started Özil on the right in four of his five starts. Wenger, of course, almost always used Özil in a primarily central role, with only occasional spells on the wing, such as early in 14/15 and during the European run last season. From his number 10 position Özil had plenty of attacking freedom and regularly ventured to the wings anyway, but he also had responsibility to move towards the centre circle and offer himself in possession when both central midfielders were on the ball. Just look at the areas and volume of his passing on Sunday compared to when Everton came to the Emirates in February.

Özil arguably hasn't been helped by Arsenal’s left side bias in recent matches. In their last three games the Gunners have found progressing the ball up the left side of the pitch a lot easier than building through the right. One reason for this may be Granit Xhaka. Xhaka has usually been the dominant presence in possession, and as a left footer he’s more comfortable patrolling the left side of the pitch and circulating the ball to that side. It’s notable that despite nominally starting on the right, a lot of Özil’s involvement against Everton still came on the left wing.

In fact, Xhaka’s preference for left sided passing, and Özil’s positioning on the right has significantly disrupted their on pitch relationship. While Xhaka didn’t have his best individual season last year, one thing he did do well was give the ball to Özil. Xhaka to Özil was regularly one of Arsenal’s most prolific pass combinations. The holding midfielder is usually Arsenal’s highest volume passer, and thus a lot of Arsenal’s attacks go through him. With so many of his passes going to Özil, it’s not a surprise the then number 11 followed him as Arsenal’s second most frequent passer in 17/18.

This season that relationship has broken off. On Sunday only 7 of Xhaka’s 82 completed passes found Özil, just under 9%. In the same fixture last season, which Arsenal won 5-1, 17 of Xhaka’s 73 went to Özil, 23%. Equally important is the location of their combinations. On Sunday the few times Xhaka did find Özil was when Özil made rare venues to the left wing. There were only a couple in the central areas of the pitch, while in the fixture last season, the majority came in those spaces. Without that direct exchange with Xhaka, the ball has to go through different routes to get to Arsenal’s number ten, and it’s not a surprise he's seeing a lot less of the ball.

It’s likely that a simple change of putting Özil back into the centre will not only prevent him from being isolated on one wing, but will also help Arsenal’s build up play and overall balance in possession. The central midfielders will have easier forward pass options, as Özil is more comfortable receiving in the number ten space than Ramsey is. If Aubameyang were to continue on the left, then getting Özil on the ball frequently in central areas could help him to operate as more of an outlet. The irony of Arsenal’s current left side bias is that while their best playmaker feels isolated on the right, their best outlet and poacher in the box is regularly involved in build up on the touchline, far from goal, and is often having to put crosses in for others when ideally he’d be the one getting on the end of moves. In these last few matches the rare times Özil has moved away from his position on the right have been some of the rare times Arsenal have looked potent going forward. His role in the build up to Aubameyang’s goal at Cardiff is an example.

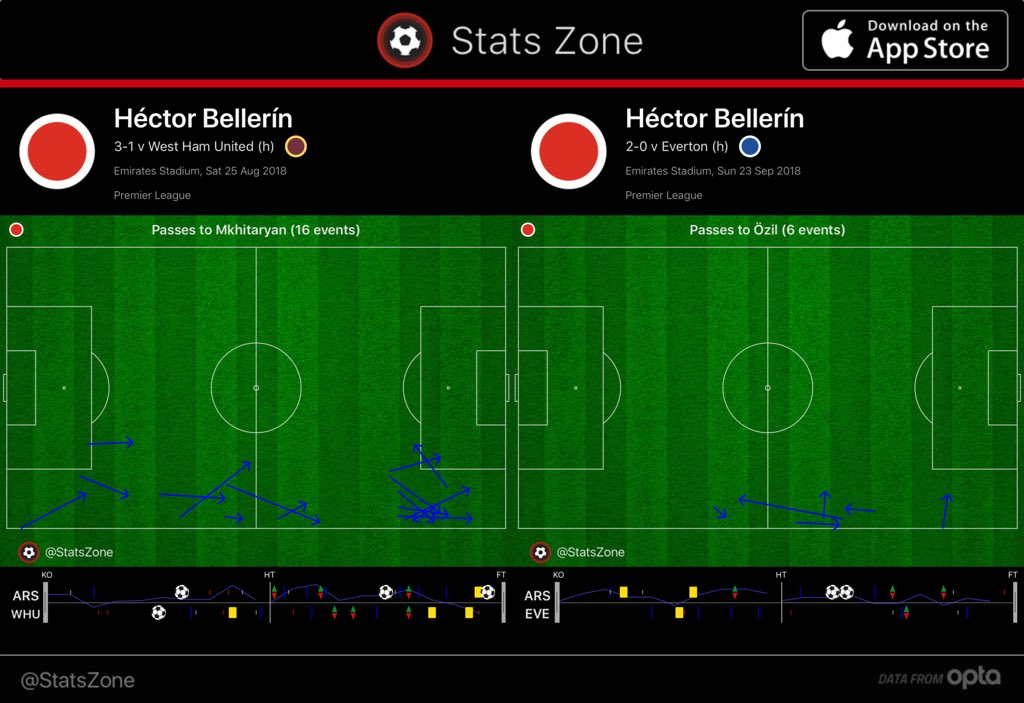

Against Chelsea and West Ham, Mkhitaryan was used on the right, with Özil central for one and absent for the other. Bellerin and Mkhitaryan enjoyed their partnership, and Arsenal did a lot more attacking down that wing in those two games. As @ThatGooner alluded to in his thread, Mkhitaryan likes to make runs behind into the channels, which creates space and allows a run for the right back to try and pick out. While Özil can make those kind of runs, it’s more of a change up option for him. He usually likes to come short and drift inside, and Bellerin hasn’t been able to build the same sort of partnership with him during build up, which has contributed to Arsenal's left side bias.

Occasionally it'll be suggested that Özil’s form last autumn was down to him playing for a new contract, and that after securing a huge wage increase, he’s reached a comfort level that is hindering his motivation. That is a possibility. But it’s also a malicious accusation to throw at an elite athlete who has worked hard his whole life on improving his craft. His Europa League performances last season also show there's still hunger there beneath his usual solemn demeanour. Given his play style, Özil should still have more years to give to Arsenal at something close to peak level. If Arsenal are to play their best attacking football, if the Unai Emery era is to become a success, or if Arsenal simply want to avoid financial disaster, it’s imperative Emery finds a way to get more out of Arsenal's highest earner, and most gifted footballer.

The most obvious reason that Özil has been shafted wide is because of Emery’s preference for using Ramsey as the number ten. In part three we’ll look at the difficulties of accommodating both Özil and Ramsey in the same team.

Oscar is on Twitter @Reunewal. Follow him there.

Mesut Özil: Beyond the Narrative

This is part one of a three part series on Mesut Ozil by Special Contributor Oscar Wood

It has not been a good few months for Mesut Özil. His 2017/18 season finished disappointingly on a team level, with Arsenal’s elimination at the hands of Atletico Madrid in the Europea League. He then became part of a political storm in Germany when he and Ilkay Gündoğan posed for a photograph with Turkish president Erdoğan. What should’ve been a forgotten matter by the time of the World Cup reared back into focus after Germany’s earliest elimination in 72 years. The lack of support for Özil within the board and the negative press that surrounded the player, which regularly bordered on the extreme and had particularly sinister connotations in relation to the player’s national heritage, cumulated in one of the more shocking international retirements of recent memory. To make matters worse, the Arsenal man has had a particularly poor start to the season, just when supporters are hoping for an uptick in fortunes for the club.

With all the negative attention that has surrounded the German in recent weeks and months, it has been easy to overlook something else. Something that might not be as obvious at the moment, but something that is just as important, if not more so, than anything else currently being said or written about the player. Mesut Özil is still Arsenal’s best player. At the moment, with him taking home a healthy £350,000 a week from the club, and his last top draw performance coming many months ago, people might scorn at the idea Arsenal’s new number ten is worthy of such a billing. But rewind eight or nine months and the narrative surrounding Özil was entirely different. With the negative energy of Arsenal fans predominantly focused on Alexis Sánchez it was easier to see the positive aspects of Özil’s play. The good will was only be helped by the building rumours of a new contract extension that cumulated with his renewal at the beginning of February. The road since has been more rocky. The burden that comes with such a wage hike started to bear heavy almost immediately, and the team overall have had few successes since their star man signed on.

That can make it easy to forget just how important Özil is to Arsenal, and how good his performances were as recently as last season. Indeed, his 2017/18 season has become more underrated with time, thanks to recency bias and a combination of on pitch factors that meant he didn’t get quite the amount of recognition he could’ve done. In the Premier League he put in many of his best performances for the Gunners, was one of the Europa League's standout players in its latter stages, and was a consistent performer whenever he got on the field at the Emirates stadium.

At face value, Özil’s eight Premier League assists represent a mediocre return for someone of his reputation as a creator. However, when it came to creating chances from open play, it was one of Özil’s best ever seasons. The 2.99 key passes per 90 minutes he played from non-set piece situations was the highest figure he’s had in a Premier League season, beating his previous best of 2.80 from 2015/16. One of the criticisms of the key pass stat (some call it chances created, they’re the same thing), and this isn’t without valid reason, is that it doesn’t take into account the quality of the chances created. Any pass that leads to a shot is one key pass, whether it’s a big chance, or a shot from 30 yards. But Özil’s expected assists per 90 figure was 0.38, which was the same figure as Kevin De Bruyne’s, who was widely cited as the league’s outstanding midfielder and creator last term. It was also higher than Özil's own figures in 14/15 and 16/17 figures (there’s no data for his 13/14 season) abut down on his astonishing 0.52 in 15/16. One thing which hurts his overall creative numbers is the fact he took fewer set pieces in 17/18. In 17/18 he averaged 3.2 corner takes and 0.9 free kick takes per 90 minutes. In 15/16 those figures were 4.3 and 1.3 respectively. His 16/17 figures were similar (they were slightly lower before that, Cazorla used to take quite a few). In other words he was taking one and a half fewer set pieces per match last season. Xhaka got three assists directly from corners last season, whereas in 16/17 he got none. Had Özil taken all the extra corners Xhaka took last season, his overall assist tally may have looked better. There isn’t open play only xA data publicly available unfortunately. But a significant reason why Özil’s xA per 90 in 15/16 (0.52) was better than his 17/18 figure (0.38) would’ve been those extra set pieces he took.

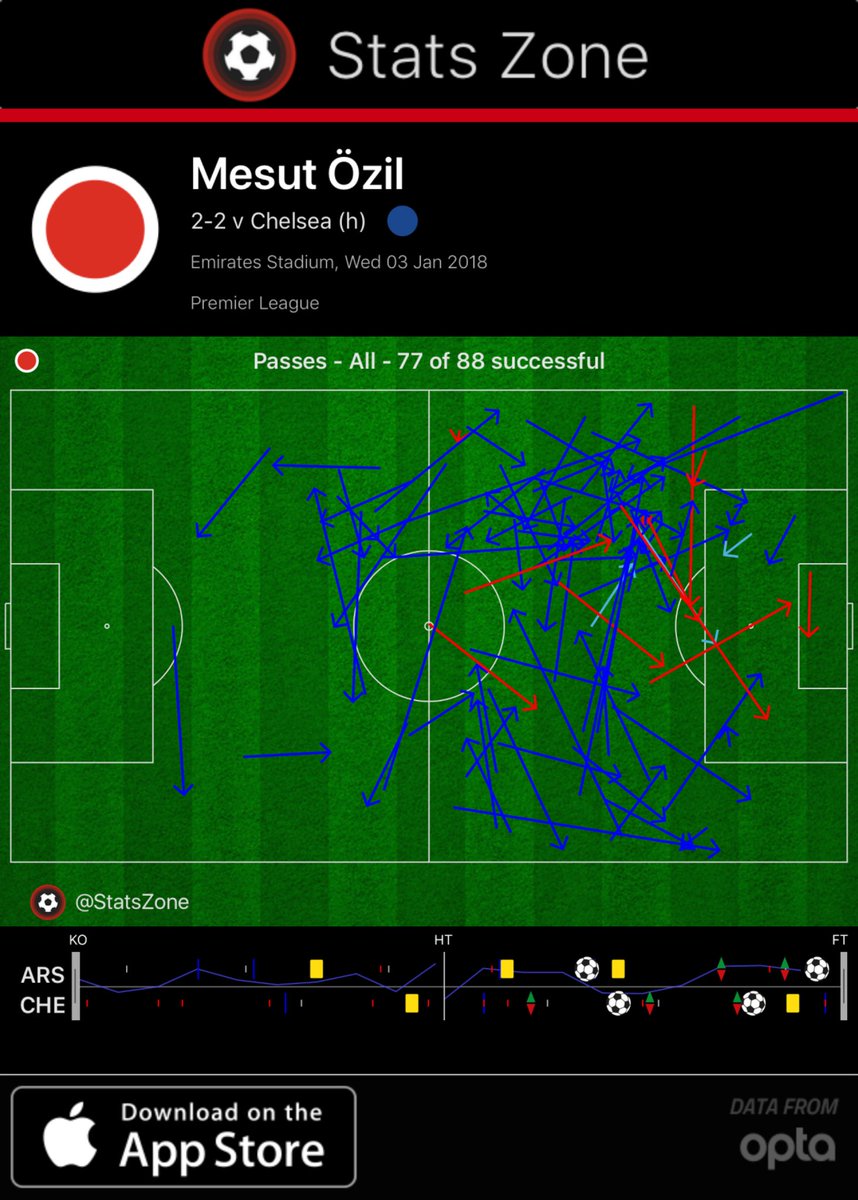

Özil’s impact doesn’t just come with the final ball, however. Last season he actually increased his already significant responsibility in Arsenal’s possession play, particularly during the part of the season when the Gunners operated with a back three. That formation left Arsenal with fewer ball playing midfielders, and Özil became a key facilitator for Aaron Ramsey to make his trademark forward runs and support the attack. In the Premier League he completed a career high 65.05 passes per 90 minutes and was one of the league's best when it came to progressing the ball up the pitch. At his peak during the season from October to the end of January, he would regularly start a passing move, keep up with the play, then lay off the final pass to finish the play, like in the clip below against Palace.

In the 2-2 draw against Chelsea, even Gary Neville was impressed by the way he took control of the match and dictated things for Arsenal. In that match he dominated possession in the final third. Özil was playing so many passes in dangerous areas of the pitch that he ended up playing 22 passes to Alexis, a remarkably high figure for a pass combinations between two forwards in a big game, which was bettered only by the 24 passes Xhaka played to Özil.

What didn’t help Özil’s cause is the perception surrounding his absences from the team in 2018. A back injury ended his club season after Arsenal’s Europa League tie with Atletico Madrid and seemed to disrupt his World Cup. Özil isn’t the only player to miss games through injury and illness, but with him there is definitely an impression that, at best, he misses games too easily, and, at worst, has excuses for him entirely fabricated so he can enjoy extra time off. When he misses games there are more tinfoil hat appearances on the Twittersphere than there are for perhaps any other player. We have to ask ourselves whether such attitudes to his absences are really fair. After missing the West Ham game Unai Emery became the third manager in recent years to excuse Özil from a game because of illness. What is more likely; three different managers deciding to give him special treatment, or him simply having a below average immune system?

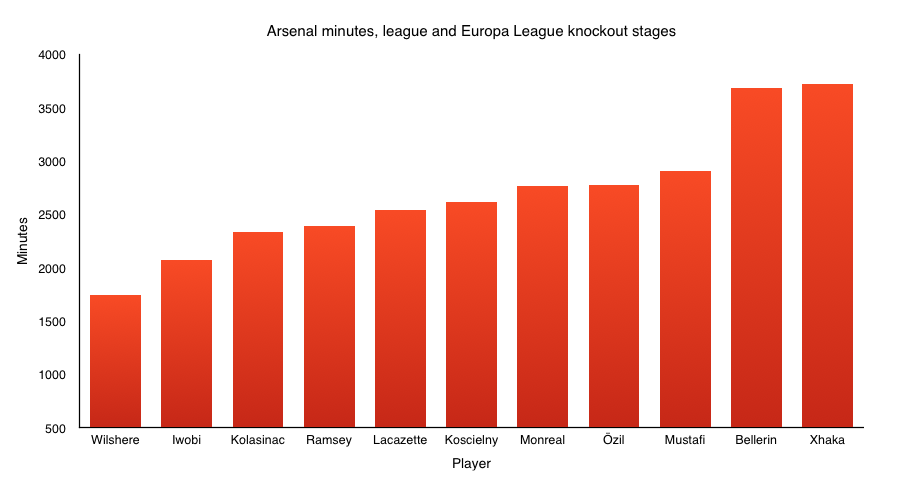

On face value Özil missed 12 league games, which isn’t great. However the majority of these came from February onwards, when Arsenal’s priorities shifted from domestic competition to their European run. He played every Europa League knockout game bar the Östersunds home tie, and was a standout player in the competition (only in the Atletico away match did he fail to put in a high quality performance). In other words, there were essentially just five games Özil missed that were important to Arsenal’s season. In the Premier League and Europa league knockout stage, the important fixtures in Arsenal's season, Özil played the fourth most minutes for Arsenal, more than the likes of Lacazette, Monreal, Ramsey and Koscielny. Missing sporadic games here and there also looks bad because of the number of different no shows, but when almost all the absences are short the collective damage is minor. Missing three one off games through illness is certainly no worse than missing five weeks with a muscle strain.

Of course, not even Özil’s biggest detractors will argue he’s incapable of doing useful things on a football pitch. The debate has always been about whether the trade offs of giving such a narrowly defined player great responsibility are worth it. Do you gain more than you lose? Özil is best used centrally rather than wide, but he can neither defend like a true midfielder, nor score like a true second striker. These traits make him something that is surprisingly common in the Arsenal squad; a player with a few elite skills who needs a fairly confined role in order to prosper to his full capabilities (I think Aubameyang and Ramsey fall into this category as well, somewhat).

Arsene Wenger clearly felt the positives of building around Özil outweighed the negatives and gave him significant freedom and responsibility to be an on pitch leader for Arsenal. Sometimes it paid off, sometimes it didn’t. Unai Emery has up till now used him in a more periphery role, which has so far failed to produce anything like Özil’s top form. But it has arguably hurt Arsenal’s overall attack as well. As of yet, the Gunners have been able to find consistent fluency without their number ten at the heartbeat of things. After a season of under appreciated heights in 2017/18,

it would be a shame if Özil’s best performances were to become purely a thing of the past under Unai Emery.

Tomorrow we’ll take a look at the beginnings of Özil’s 2018/19 season, and why the German has so far struggled under Unai Emery.

Oscar is on Twitter @Reunewal. Follow him there.